Redburn Reads, April 12, 2023

Friends,

What makes for good journalism?

Friends,

What makes for good journalism?

I’m going to wade into a issue where there are no easy answers. I certainly don’t have any. But I think the question above is a different way of framing a number of debates about “objectivity” and bias in the mainstream press. And it also provides a useful way of thinking about the difference, say, between the way the New York Times and the Washington Post treat their readers, and the way Fox News speaks to its audience.

Marty Baron, the former editor of the Washington Post, Boston Globe and Miami Herald, recently wrote an essay defending the practice of

“objectivity” in journalism.

We want objective judges. We want objective juries. We want front-line police officers to be objective when they make arrests and detectives to be objective in conducting investigations. We want prosecutors to evaluate cases objectively, with no preexisting bias or agendas. In short, we want justice to be equitably administered. Objectivity — which is to say a fair, honest, honorable, accurate, rigorous, impartial, open-minded evaluation of the evidence — is at the very heart of equity in law enforcement. . .

Most in the public, in my experience, expect my profession to be objective, too. Dismissing their expectations — outright defying them — is an act of arrogance. It excuses our biases. It enshrines them. And, most importantly, it fails the cause of truth.

Increasingly now, journalists — particularly a rising generation — are repudiating the standard to which we routinely, and resolutely, hold others.

These critics of objectivity among journalism professionals, encouraged and enabled by many in the academic world, are convinced that journalism has failed on multiple fronts and that objectivity is at the root of the problem. . .

Ultimately, critics consider the idea of objectivity antithetical to our mission overall: The standard is a straitjacket, the argument goes. We can’t tell it like it is. The practical effect is to misinform. Moral values are stripped from our work. The truth gets buried.

Marty is a friend and former colleague. So I find it particularly hard to be “objective” about his piece. For one thing, I agree with much of his argument. But I also find it wanting in some ways, since seeking even the most fair-minded, rigorous journalism doesn’t necessarily provide much guidance on what we should be reporting on and how much to emphasize one story or another.

I’d like to illustrate my point with an example from my own area of expertise: economics reporting. In the last couple of years, much of the focus of economics coverage has been on the rise in inflation. This is perfectly understandable and certainly justifiable. After decades of low inflation, prices started rising much faster, setting off alarm bells at the Federal Reserve, which began to sharply raise interest rates. Higher prices affect nearly all Americans, and it would be irresponsible not to write extensively about the issue. Indeed, journalists are duty bound to focus on what’s new and different in the world around us.

But over the same period, far less attention has been devoted to the continuing decline in unemployment, the improvement in job prospects for lower wage workers, and the substantial benefits of running an economy at what amounts to nearly full utilization of our human and physical resources – perhaps even temporarily a little beyond the capacity of them.

It seems to me that the mainstream media, even as its corps of very talented economics reporters has provided plenty of useful information, has gotten the balance between the risks of inflation and the rewards of low unemployment off. And that imbalance has been exaggerated even more by the pervasive coverage by political reporters, cable TV commentators, and the like, which has continually raised alarm bells about inflation and the threat of a recession even as the economy has delivered a remarkably high level of jobs and steadily increasing income to most American households.

Of course, partisan divisions and a right-wing drumbeat from the Murdoch media explain much of the public pessimism about the economy. And there are certainly plenty of economic problems, starting with a staggering gap in incomes between the rich and the rest of us. But “objective” journalism also shares some responsibility for the widely held belief that these are not generally prosperous times.

It’s one example of where journalism has fallen short of being as good as it should be, partly because of the desirable tendency among reporters and editors to focus on what’s going wrong rather than what’s going right, but also because inflation is an issue of greater concern to greater numbers of people, particularly the generally comfortable middle class and business elites than is unemployment, which tends to fall hardest on the poor and insecure.

There are other cases outside my own personal experience: the oft- mentioned question, for example, of whether the New York Times swayed the 2016 election by over-playing Hillary Clinton’s lapses in handling her emails during the 2016 election campaign while publishing an unintentionally misleading story that downplayed the FBI’s investigation of Russian support for Donald Trump.

On this subject, Matt Yglesias, writing on his Substack site, has an insightful piece arguing that the whole notion of objectivity in journalism has changed because the audience has changed and viable journalism requires a different business model than in the past. I’m quoting it at length, in part because many of you don’t have access to his site. Matt focuses on the proliferation of new forms of journalism, but it’s also true that even mainstream organizations, still relying on the cornerstones of fairness and impartiality, read far differently today than they did even a decade ago, much less than in the era of “just-the-facts” journalism of the two decades after World War II.

Please keep reading below: I couldn't eliminate a formatting gap in my text.

In late March, the former Washington Post editor Martin Baron wrote a stirring defense of journalistic objectivity in his former paper.

The piece is shaped by the contours of his various fights over the years with former Post reporter Wesley Lowery. Baron doesn’t mention the dispute directly, and Lowery says he has simply avoided addressing those criticisms, which related more to the practice of objectivity than to the theory. Most of the replies to Baron that I’ve seen take some version of this line, though Brian Beutler offers what I think is a smarter criticism, namely that the practice of journalism inherently involves lots of questions that don’t have an objective answer. . .

I think the bigger issue here is that the journalistic values of American newspapers in the second half of the 20th century reflected first and foremost their business model. Both the good and the bad were fundamentally tied to business considerations —the “Chinese Wall” between business and editorial was itself part of that. And whatever consensus develops around objectivity in journalism going forward will also need to reflect the realities of modern business considerations. . .

These same considerations also dictated the practical realities of ideological bias in journalism. The big television broadcast networks operated in a low-competition environment of three giant franchises. Newspapers operated in locally segmented markets where there was usually no direct competitor (maybe in a giant city there would be one competitor).

The aim was to reach as broad an audience as possible, which in practice meant not so much avoiding ideological bias as trying to make sure that your biases were in line with the audience. Even in the highly polarized landscape of 2017, the optimal way to pursue that strategy would have been with a kind of centrist ideological bias.

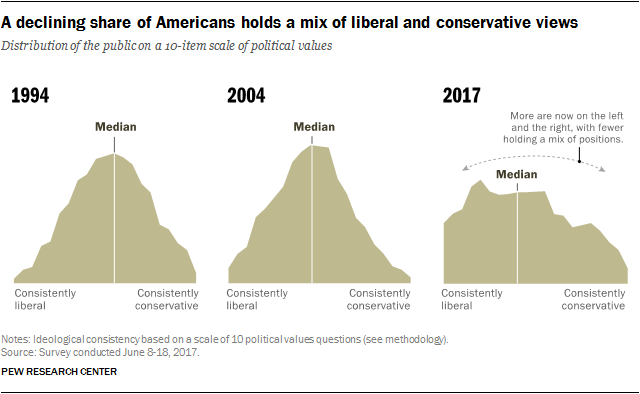

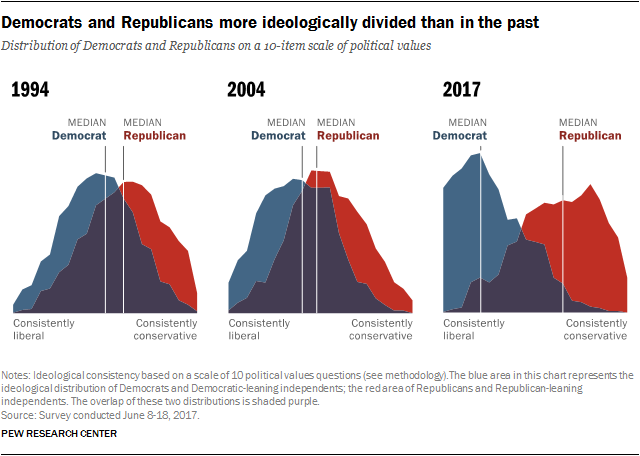

As recently as the mid-90s, the underlying distribution of American public opinion was in fact much more centrist, with the median Democrat not that different from the median Republican and lots of overlap. If you pitched down the middle, you’d please the largest possible chunk of the audience and stay on decent terms with key elites from both parties.

The causation went both ways, with a relatively non-polarized public opinion encouraging centrist media while centrist media helped discourage polarization of public opinion. But starting with AM talk radio in the 1980s, Fox News in the 1990s, and then the internet in the 2000s, the media landscape became much more open and competitive. And the news landscape started looking more like the newspaper landscape in the UK (which had multiple competitive national newspapers) had always looked. Outlets tried to define their niches more precisely, to be not just “a news source for people who live near Albuquerque” but “a news source for people like you.” Generic doesn’t work well when you’re jostling amongst a crowd. . .

None of which is to say there’s no market for conservative content; there’s obviously a huge market for conservative talk radio, and there’s a reason Fox News is the most popular cable channel. But successful conservative media tends to be anchored by small numbers of charismatic stars operating in a hyper-political context and a primarily audiovisual medium. The realm of “written recaps of television shows” is distinctly left-skewing not because journalistic values have collapsed, but because the easiest way to churn out content is to have mostly-liberal people writing for a mostly-liberal audience.

I’m not suggesting that nothing has been genuinely lost in the displacement of the objective ideal.

But it really is worth saying that the ideal of the newspaper that speaks to everyone and for everyone wasn’t just a conceptual ideal, it was a business model. And to be clear, like objectivity itself, the universal newspaper was a regulative ideal, not a reality. Even in a town with no competition between newspapers, lots of families didn’t subscribe to the newspaper. But the goal was that everyone should subscribe, that the paper — the paper — was a big bundle of information services designed to be both comprehensive and inoffensive, and in principle, everyone should get it.

That doesn’t make sense as a contemporary business aspiration, in part because the landscape is so much more competitive and in part because the core information utility service is gone. . .

Alternatively, a publication might (like this one!) have a business model that doesn’t rely on reaching a mass audience. Either way, though, while there’s a lot one could reasonably ask of a publication, it’s bound to end up being very different in tone and approach from the newspapers of “the good old days.” There’s just no way to keep the product similar while the underlying business model is revolutionized.

This mostly makes me wish that everyone would spend a little less time complaining about media that they think is bad and a little more time thinking about how to support media that they think is good. Spend less time getting mad online or marinating in anxiety about stuff you can’t control. Try to think of some questions you’re sincerely interested in and seek out the places that are doing the best job of informing you about them and try to support them financially. In a changing world, that’s the best we can do.

Perhaps the greatest loss in the collapse of the ad-supported newspaper is local news. Chains like Gannett and news organizations gobbled up by private equity firms have decimated newsrooms. Which is why it is particularly important “to seek out the places that doing the best job of informing you about them and try to support them financially.”

In Nieman Reports, a publication about journalism, Jon Marcus looks at a particularly encouraging trend: the support fledgling online publications are receiving from retired journalists.

Rather than moving to retirement communities and settling in beside the pool or playing pickleball, retired journalists are stepping into news voids nationwide, launching local and regional media outlets or serving on their boards, mentoring young journalists, advocating for press freedoms, and continuing to gather and report information not otherwise being covered. In some cases, they’re returning to their roots in local news, spending their retirements reviving the kinds of local newspapers and news sites that have been particularly hard hit by the consolidation of the industry by big media companies and hedge funds.

These retirees include everyone from a onetime local sportswriter in Washington state to former top editors at The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Reuters, a retired senior editorial director at CNN, familiar names from NPR, the ex-editors of the San Diego Union-Tribune and Miami Herald, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalists, a retired AP bureau chief and a former top executive at Hearst. Many are in their 70s or 80s.

Many also share a collective frustration with the decline of the profession in which they spent careers that date back to a time when media organizations were flush with resources and influence.

“If you can do something to help reverse that tide, you do it,” says Walter Robinson, the former editor of The Boston Globe Spotlight Team, who has taken on a second career helping set up nonprofit community news sites, mentoring younger journalists, and serving on the board of a government accountability and First Amendment coalition.

“I had a great run and a lot of good fortune, and I just feel I have an obligation to give something back,” says Robinson, who is 77, of his continued involvement in the cause of journalism. “A lot of people I know who are my age have the same impulse.” . . .

After decades of having to be available around the clock and holidays, many journalists don’t have lots of hobbies they’ve been waiting for retirement to tackle, says Bob Davis, a 72-year-old retired Wall Street Journal senior editor who now mentors Report for America reporters, freelances for The Wire China, and edits for the Prison Journalism Project, which trains incarcerated people to be journalists.

“My friends play pickleball, but honestly, is that something I want to do?” says Davis. “I half-jokingly equate pickleball with death. The guy with the sickle in the Bergman movie? I equate pickleball with that.”

Some of these former journalists say they tried other things before they drifted back into the fold. When they retired to Asheville, Kestin and Gremillion volunteered at a food bank, packing potatoes and cans of beans, but eventually realized they could contribute more through journalism. (He also tried golf, he says, but “the dirty little secret is that I could never break 100.”)

I can break 100 but I’m also hoping to do what I can to support a new non-profit local journalism site in my community of Plymouth, Mass.

For all the challenges facing modern journalism, its survival is crucial to the survival of American democracy. That’s why we care so much about making it better. By contrast, though, I don’t think the same thing can be said of the once self-proclaimed “fair and balanced” presentation offered by Fox News. Most news organizations are businesses, and they must satisfy an audience to survive. But the way they go about it can be starkly different.

As Jim Rutenberg explains in a brilliant piece for The New York Times Magazine, Rupert Murdoch, the owner, is far less interested in delivering some semblance of reality to his audience than he is in pandering to its demands for a fun-house mirror image of the world that conforms to their own prejudices.

For most of my career as a reporter, I’ve been tracing Fox’s long journey to a dividing line: On one side, journalism, constitutionally protected, even in its nastiest, most slanted and ideological form as part of the brutal scrum of democracy. On the other side, knowing lies, reckless disregard for the truth — the “actual malice” that is at the heart of the Dominion case. The court will decide if Fox crossed that line. But the newly available records show what drove Fox, and its powerful founder, to the very edge of that line, if not beyond: an audience that has reliably delivered influence and profits for decades. Now, in the age of social media and powerfully attractive disinformation campaigns, that audience could instantly move on to even headier stuff from even more adventurous competitors.

Murdoch has always understood the value of his audience, in terms of power and in terms of money. For him the choice may be simple. In his Dominion deposition, a lawyer asked him why he did not want to “antagonize” Trump after the election. “He had a very large following,” was Murdoch’s characteristically terse response. “They were probably mostly viewers of Fox, so it would have been stupid.”

Trump, with his flagrant disregard for facts, presented every news organization with significant challenges. For Fox, the problem was even trickier. Trump had a particularly strong hold on its core audience members. Would Fox follow them down the rabbit hole? By the time he clinched the 2016 Republican nomination, they had choices. For the first time, there were other options for conservative news consumers on television — Newsmax, which Ruddy had brought to cable in 2014, and One America News Network, which made its debut in 2013. The new networks were “barely a blip,” one Fox executive would say dismissively. In the early summer of that year, Ailes came under scrutiny for serial sexual harassment and abuse at the network, which would lead to his ouster; after the Murdochs forced Ailes out that July, he became an informal political adviser to Trump. Hannity was acting as an informal adviser to Trump, too, crossing Ailes’s onetime line. Quietly, that August, the network dropped its defining slogan: “Fair and Balanced.”

The ratings soared higher, and more obstacles fell away. James Murdoch, then in a contest with his brother, Lachlan, to succeed Rupert at the top of the empire, argued that Fox should impose stricter journalistic standards and dial down its pro-Trump coverage to avoid brand troubles for the Fox Corporation’s movie business and ease any plans for expansion. Rupert picked Lachlan, who thought holding the current course was a no-brainer. Murdoch sold the studios to Disney, and James went out on his own. Fox News became an increasingly important profit driver of the family business.

Fox’s opinion hosts were drawing ever closer to Trump’s inner circle, and their bosses seemed less willing than ever to pull them back. In one especially striking moment at a rally for the 2018 midterm elections, Hannity stood next to Trump at his presidential lectern, pointed to the reporters in the back of the hall — including Fox’s Kristin Fisher — and called them “fake news.” The reporters on the news side were furious. The network issued a tepid statement that it did not “condone talent participating in political events.” During a lunch with Suzanne Scott and Jay Wallace, Fox News’s executive editor, the network’s leading news anchors — among them Chris Wallace, Bret Baier and Martha MacCallum — urged the bosses to bring disciplinary action. But nothing appeared to come of it. Hannity continued to help Trump into the next campaign year, even as the brand-name journalists were heading for the door. Carl Cameron, a senior political correspondent, had already left in August 2017, later saying the network’s journalists were being drowned out by “partisan misinformation” from the opinion side. The anchor Shepard Smith left in 2019 and would go on to cite similar complaints.

This was the company, and the audience, that were confronted by Trump’s election lie in 2020. The president could create and distribute a story in real time, and Fox could track the viewer response minute by minute. What it found was exactly what Trump intuited after Romney’s loss in 2012: The audience wanted the election lie. When Fox stopped giving it to the audience, there was an instant falloff. That falloff came quickly after Fox News became the first network to call the state of Arizona for Biden in 2020, undermining his contention that he was winning. The president and viewers were furious, and competitors were ready to take them away. . .

The network says it has installed new editorial oversight across all its platforms. But that system will be up against the network’s very nature. The facts are clear to all. “Trump insisting on the election being stolen and convincing 25% of Americans was a huge disservice to the country,” Murdoch wrote to Scott on Jan. 20, 2021, the day Biden became president. “Pretty much a crime. Inevitable it blew up Jan. 6th.” But what will Murdoch and his employees make of the facts? What will happen when everything is on the line again and that audience wants Trump on Trump’s terms again? Fox could deny them. It could promote the truth, inform its viewers and serve the First Amendment role that the justices in Times v. Sullivan so carefully defined and protected. But that might antagonize Trump and his audience. And, at least as Murdoch had explained to Dominion’s lawyers, doing that would be stupid.

And Rupert Murdoch is certainly not stupid. Which is why Fox produces so much bad journalism.

Take care,

Tom